By Osita Mbonu

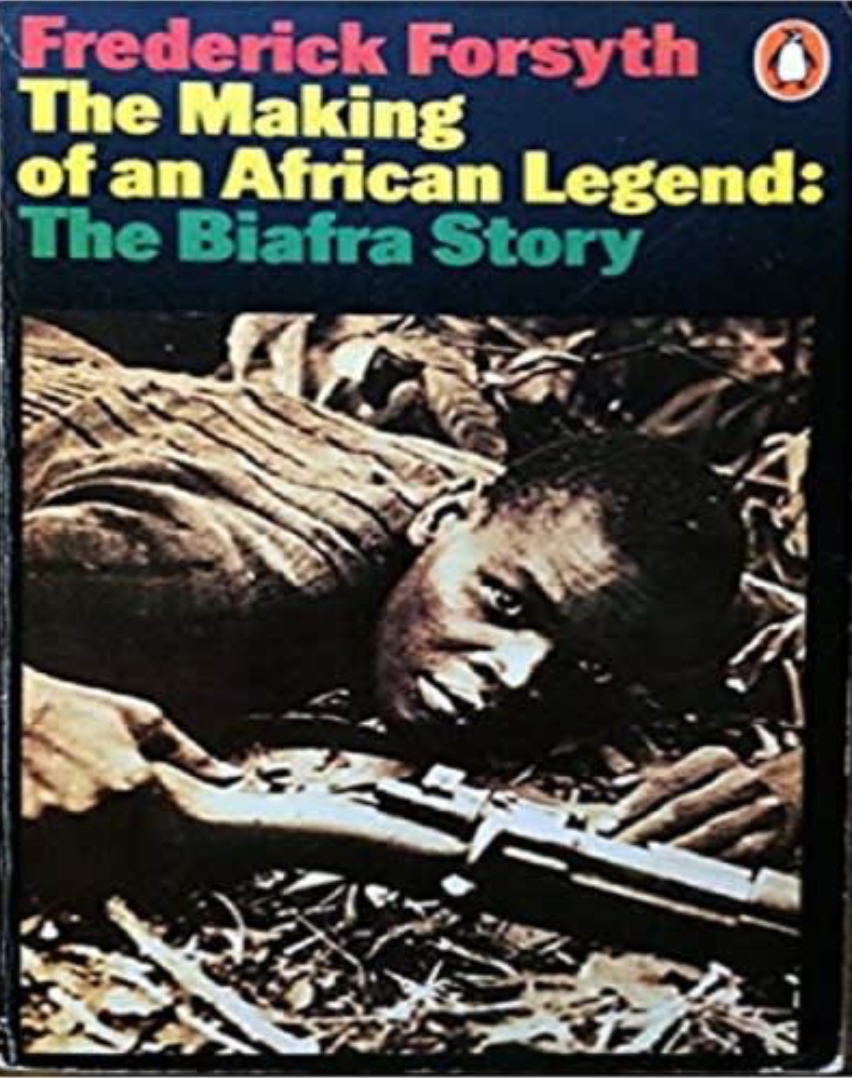

The passing of Frederick Forsyth (August 25, 1938 – June 9, 2025) is no longer breaking news. One of the best ways to honor his memory now is to reflect on the rich trove of literary works left behind by this prolific and empathetic author. Forsyth is renowned for his gripping thrillers such as The Day of the Jackal, The Odessa File, and The Dogs of War, as well as his insightful non-fiction work, The Making of an African Legend: The Biafra Story.

In keeping with the journalistic principle of proximity, Forsyth’s book on the Nigeria-Biafra War, The Making of an African Legend: The Biafra Story, holds special significance for readers in this part of the world. It offers a compelling and nuanced perspective on a pivotal chapter in African history, making it essential reading for anyone interested in the region’s past.

Combining thorough research with gripping storytelling, he authored a series of novels that have sold over 75 million copies worldwide. His work earned him numerous accolades, including a CBE in 1997 and the prestigious Diamond Dagger award from the Crime Writers’ Association.

Born in Ashford, Kent in 1938, Forsyth initially served as a fighter pilot during his national service. However, when the Royal Air Force could not guarantee that he would remain in the cockpit, he decided to explore the world beyond military service.

After spending some time in East Germany, Forsyth joined the BBC. In 1967, he was dispatched to Nigeria to cover the Biafran conflict. He arrived in the eastern region, newly declared independent, just three days after the Nigerian federal government launched its invasion. At the time, he had been informed that the military would quell the rebellion within weeks.

“My assignment was to report on the unstoppable advance of the Nigerian army,” Forsyth later recalled. “But that did not happen. Naively, I reported this. When my broadcast aired, our high commissioner lodged a complaint with the Commonwealth Relations Office in London, which then pressured the BBC. They accused me of having a pro-rebel bias and summoned me back to London.”

Frustrated by the BBC’s unwillingness to question the British government’s support for the Nigerian regime, Forsyth resigned and returned to Biafra in 1968 as an independent journalist. There, he played a key role in exposing the famine that horrified the global community and began working with MI6. Although Forsyth always denied being a spy, he revealed in his 2015 memoir, The Outsider, that he had been an intelligence “asset” for over two decades. Speaking at a Guardian Live event, he explained, “It was the Cold War. Much of British intelligence’s strength came from volunteers. A businessman attending a trade fair in a restricted city might be discreetly asked to carry an envelope back home—that was the kind of errands I ran.”

As the war drew to a close in December 1969, Forsyth returned to the UK, finding himself without employment, prospects, accommodation, transportation, or savings. In a bid to earn money, he chose what seemed the most unlikely path: writing a novel.

“The Biafra Story” by Frederick Forsyth is a compelling and groundbreaking non-fiction account of the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), focusing on the secessionist attempt by Biafra. As one of the earliest eyewitness reports from the Biafran perspective, it offers a vivid, detailed narrative of the brutal conflict, including military actions, relief efforts, and the immense suffering caused by starvation and violence.

Forsyth’s work stands out for its passionate and forthright style, driven by his outrage at the extremes of human violence and the duplicity of Western governments, especially the British, who tacitly supported the Nigerian government during the war. His reporting is marked by a clear bias toward the Biafran cause, reflecting his commitment to exposing what he saw as suppressed truths and moral failings in international politics.

The book not only documents the war’s events but also highlights the humanitarian crisis, notably the starvation of children, which brought global attention to the conflict. Forsyth’s background as a journalist and his firsthand experience on the ground lend authenticity and urgency to his narrative.

A revised edition published in 1977 expanded the original manuscript to include post-war developments, enriching the historical context and making the book a significant resource for understanding this pivotal African conflict.

Overall, “The Biafra Story” is a powerful, insightful, and essential read for those interested in modern African history, war journalism, and the complexities of post-colonial conflicts. It marks Frederick Forsyth’s transition from journalist to acclaimed author and remains a classic of war reporting.

Frederick Forsyth’s eyewitness account in The Biafra Story deepens understanding of the Nigerian Civil War by providing a rare, on-the-ground perspective from within the Biafran rebel enclave during the conflict. His reporting captures the intense human suffering, particularly the starvation crisis, and the brutal military tactics used by the Nigerian federal forces, including the use of mercenary pilots and air attacks. Forsyth also exposes the political complexities and international duplicity, notably the covert support of Western governments like Britain for the Nigerian government despite public neutrality.

His narrative goes beyond official histories by highlighting the humanitarian disaster and the emotional impact of the war, which is often underrepresented in conventional accounts. As one of the earliest and most detailed eyewitness reports, it enriches the historical record with vivid detail and a passionate critique of the war’s causes and consequences, thus offering a more nuanced and humanized understanding of the conflict.

“The Biafra Story” offers a compelling critique of Western governments’ roles in the Nigerian Civil War by exposing their duplicity and self-interest, particularly highlighting the British government’s tacit acceptance and active support of the Nigerian federal forces despite widespread atrocities. Forsyth details how British civil servants influenced Nigerian policy with a condescending attitude toward African perspectives and how arms shipments from Britain to Nigeria increased significantly after the war began, contradicting official claims of neutrality. The book reveals how British business interests, especially in oil, aligned with political decisions to support Nigeria, prioritizing economic gain over humanitarian concerns.

Forsyth also underscores the deliberate misinformation campaigns by Western governments to maintain public support for their policies, even as images of starving Biafran children sparked global outrage. The British government’s refusal to ease blockades or facilitate adequate relief efforts, despite public protests, exemplifies this moral failure. By combining vivid eyewitness testimony with sharp political analysis, Forsyth exposes how Western complicity exacerbated the conflict and humanitarian crisis, making his book a powerful indictment of Cold War-era realpolitik and colonial legacy in Africa.

Frederick Forsyth chose to return and expand his original report after the Nigerian Civil War to provide a more comprehensive account that included post-war developments and to further expose the humanitarian crisis and political complexities he had witnessed firsthand. The expanded edition allowed him to deepen the historical context, highlight ongoing consequences of the conflict, and reinforce his critique of Western governments’ roles, especially the British government’s complicity. This broader perspective enriched the narrative beyond immediate war reportage, making the book a more significant and enduring resource on the conflict.

Forsyth’s eyewitness account in The Biafra Story both challenges and complements other eyewitness reports by combining personal observation with information gathered from local sources, reflecting what scholars describe as “firsthand experience” and “firsthand access.” His perspective is deeply engaged and emotionally charged, emphasizing the humanitarian crisis and political duplicity, which may contrast with more neutral or official accounts that downplay these aspects. This aligns with the understanding that eyewitnesses often see different facets of an event based on their position and access to information, leading to varying but valuable narratives.

Forsyth’s account is vivid and detailed. His direct presence in Biafra and his detailed reporting provide a critical, immersive viewpoint that enriches the historical record beyond detached or secondhand reports. Thus, his narrative challenges official Western perspectives by revealing overlooked realities, while supporting the broader mosaic of eyewitness testimonies that together offer a fuller picture of the Nigerian Civil War.