“Swift as lightening, the policeman kicked Chima’s two legs off the ground. Another hefty man joined him. Together, they flung Chima up into the air. As he was landing on the floor, they kicked him simultaneously with jackboots, forcing him to crash on the floor with his right hand. The hand dislocated from the wrist.”

“A lot of suspects have been summarily executed here for such reasons. Nobody will ask any question. The suspect escaped from custody and got shot in the process, full stop.”

“They were asleep that night when they heard gunshots. Some men ran into the uncompleted building followed by another group of men spraying bullets all over the building. Chima laid flat on the floor wedging his head into a nearby stone. But Chukwuma, on hearing the gunshot and seeing men running into the building, jumped up trying to run out of the building. The bullets cut his body into pieces. He shouted, fell down, and laid still.”

“One of the policemen spoke to a junior officer. The junior officer raised his gun, aiming at Chima. ‘Please don’t kill me. I am not a thief. Mohammed Mogagi, your colleague here knows me,’ he told them.

The junior officer lowered his gun and looked up to his boss. The boss signaled him to wait.

‘Did you say Mohammed knows you?’ the boss asked Chima.

‘Yes sir.’

‘Go and call Mohammed,’ the boss said to one of his men.

The man hurried out to the office blocks and came back shortly. ‘Sir, Mohammed has not reported for duty today.’

‘Return him to the cell.’

They dragged Chima back to the cell.”

Lagos was actually in crises. There was petrol scarcity, removing vehicles from the road. Oil workers were on strike. And actually, people were running away from Lagos. Before midnight that day Chima managed to locate the house in the address he had with him. From that night, Chima began to have a participant observation of a new level of human suffering. He had thought he was suffering until he came to Lagos.

Most people lived in one squalid room accommodation and they hardly had something to eat. The toilets and the bathrooms Chima saw and used in Lagos frightened him. The bathrooms were so small that one hardly could turn without one’s body touching the wall, the four walls carrying the dirt of several decades, turned into a jelly mass resembling a hundred years of piled up human phlegm released from coughs.

Chima knew he had a mission to accomplish, an important mission involving life or death of his younger brother. Luckily for him, the owner of the house where he was staying – an Umuogu man – had no intention of running away from Lagos. The following day Chima began to look for his brother, Dikmpa.

The Umuogu lady who had brought the bad news of Dimkpa to them at home took Chima to the high court in Ikeja where Dimkpa’s case was coming up. They said nobody was allowed to see him where he was detained. It was said that Dimkpa had stolen some money belonging to a rich man and the rich man had vowed to send him to the grave.

Chima was outside the court premises when a bus arrived with armed policemen. He did not recognise his brother, Dimkpa, when he saw him bound with handcuffs and chains.

The policemen did not allow him to speak to Dimkpa until he gave them some money. As the two brothers stood face to face with each other, tears flowed towards their eyes.

‘What put you in this type of condition, Dimkpa?’ Chima cried.

‘There is a man that has vowed to kill me. He owed me, so I took his money. I have even returned the money to him, yet he is still bent on killing me. There is nothing we have not done to pacify this man. Everything has failed. That is why I sent the message. Chima, the place they are keeping me is not a place one can survive after few days. But I’ve been there now for four months. As you are looking at me, you can see that I can die at any moment. I wish Papa was still alive, Chima. But I am glad you are here. We all hated you because you are an achiever. Something tells me you can let me off this hook. I don’t know how you are going to do it. But it’s something you have to do for me, Chima. I would do the same thing for you, you know?’

Chima nodded his head in agreement. ‘Who is the IPO of your case among those policemen?’ he asked Dimkpa and he showed him the one. Chima made a mental note of the policeman’s face.

‘Please, Chima, I am very hungry. I have not eaten anything for a very long time. Could you buy something for me to eat?’ Dimkpa said.

Chima bit his lips. More tears dropped from his eyes. He ran down to a roadside food seller and bought plenty of food for his brother.

His case was adjourned to another date. Dimkpa was dumped back into the police van, ready to be taken back to detention cell. Courageously, Chima walked down to the IPO as he was about to enter into the front seat of the police van.

‘I am Chima Duru, sir. Dimkpa is my younger brother. I would like to speak with you, but not here or now.’

The police officer projected his bloodshot eyes on Chima, assessing him, probing him. Perhaps, sensing no danger in Chima, the IPO said: ‘Mohammed. SARS,GID.’ And the van screeched out of the court premises, taking Dimkpa along with them to a place unknown to Chima.

There was no petrol, and therefore not many vehicles on the road. However, the next day, after much struggle and inquiry, Chima got to the General Investigation Department in Ikeja. But visitors were not allowed to enter into SARS department in connection with any detainee. ‘Whom do you want to see there?’ the tough-looking riot policemen at the gate asked Chima.

‘Mohammed,’ Chima answered.

‘Why do you want to see him?’

‘I am a university student, sir. He had asked me to come and take some money when I am going back to school,’ Chima said, feeling as uncomfortable as he had never felt in his whole life.

‘Where is your school ID card?’

Chima produced his school ID card. The mobile policeman perused the ID card. Then he searched Chima and lifted the wooden bar at the counter. Chima entered and walked down towards SARS, unsure of his footsteps.

He walked into an office and asked a man about Mohammed ‘Do you have a matter here?’ the plain clothe policeman asked Chima

Reluctant to continue the lie, Chima said: ‘Yes.’ Swift as lightening, the policeman kicked Chima’s two legs off the ground. Another hefty man joined him. Together, they flung Chima up into the air. As he was landing on the floor, they kicked him simultaneously with jackboots, forcing him to crash on the floor with his right hand. The hand dislocated from the wrist.

Several other policemen joined them. They carried Chima, opened a cell, and dumped him on top of many naked wounded criminals. The inmates made way for Chima on the scarce floor space. ‘Oh, why should they beat this man like this now?’ an inmate said as Dimkpa rushed to hold his brother, Chima. They had been watching the beating through the perforated blocks of the cell.

‘Dimkpa, is this where you are?’ Chima said, tying to struggle up. But his right ankle had been injured also.

‘I am sorry, Chima. I am the cause. But you are strong.’

‘You are not supposed to be here, Dimkpa. Papa had a great plan for you, for all of us.’ Chima sniffed.

‘Don’t worry, Chima. The important thing for now is how to get you out. Two of us can’t be inside this place at the same time. If that happens, that means we are finished.’

‘They took everything I had with me, including my school ID card. I think they will release me as soon as they see the ID card,’ Chima said softly.

‘Chima Duru!! Who is Chima Duru!!’ a plain clothe officer shouted, clanging open the iron gate of the cell.

Chima limped out. The policeman helped him, telling him sorry. They entered another office and he saw Mohammed.

‘You did not sustain the strategy that brought you so far. Otherwise you would have safely gotten to me without anybody beating you like that. This place is strictly out of bound to members of the public. However, I am very sorry. They saw your school ID card. You are from OAU.’

‘Yes sir.’

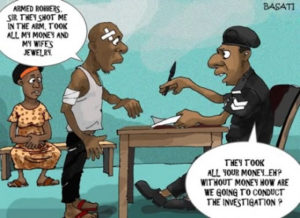

‘It’s good you are here, because when we bring suspects here and nobody comes looking for them, that’s how we know they are actually bad people. A lot of suspects have been summarily executed here for such reasons. Nobody will ask any question. The suspect escaped from custody and got shot in the process, full stop. Your brother is still alive today because I think he has no business being here. He looks different from the rest that come here.’

‘His father was the Director of Public Prosecution in my state. He died a few months ago,’ Chima said.

The IPO shook his head sympathetically. ‘I am sorry about your father. Again, it’s a good thing you are here. I couldn’t have been able to guarantee his safety after now if no one had still come for him, especially with the looming political crises in the country.’

‘Where is his case file?’ Chima asked carefully, remembering the dream he had in Umuogu in which he saw his father talking about case file.

‘Are you a law student?’

‘No sir.’

‘Well you sounded like one. The file is with me. What do you intend to do with it?’

‘Sir, I grew up watching my father save many innocent persons from execution through their case files.’

‘In that case you have to see the DPP in the Ministry of Justice at Alausa. But he cannot help you if I don’t send a copy of the case file to his office asking for his advice.’

‘Will you send the file?’

‘Yes, if you want me to. But it will cost you fifty thousand naira.’

Chima was jolted up from the chair. ‘Sir, I came to Lagos with only six thousand naira. And the whole money left with me now is not up to three thousand.’

Mohammed stood up and left the office. He entered an unmarked police pick-up van outside and drove away.

Chima waited there until dusk was approaching before he became convinced that Mohammed wasn’t coming back. Then he came out from the GID and walked towards the railway near Agege Motor Road. The bus stop was filled with people who had managed to come out in the morning, but could no longer find transport back home as a result of the fuel scarcity.

Tired, hungry and confused, he sat on a stone under a nearby tree, watching people as they struggled for the few buses that managed to come out. Some bricklayers were also washing their spades, trowels and head pans in a building under construction. An honest means of livelihood, no matter how poor, is better than a life of crime, Chima reflected. He could not understand how anybody could choose crime in preference to millions of honest labours in the world. He could not understand how someone who was born a king would choose to walk through life on hands and knees.

It was getting too dark. There was not even a single commercial vehicle on the road any longer. People began to trek, that is, people who knew where they were going. Chima joined them. Soon he fell into conversation with a young man who was also trekking. ‘I am new in Lagos. I am staying with my brother at a place called Ilasa. I came out in the morning with a public transport. But as we are trekking now, I will not be able to know the place,’ Chima told the young man.

‘Don’t worry. I am also going to Ilasa.’

It was past midnight before they got to Ilasa. Chima was surprised to learn that the young man was one of the men he had seen washing their bricklaying tools at the site of the building under construction at Agege Motor Road.

‘I am a graduate of economics from UNN, Nsukka.’ The young man, Chukwuma, said

‘And you are doing bricklaying work?’

‘It’s not even a bricklaying work. I carry blocks and cement mixed with sand and concrete. It’s five years now since I graduated. I’ve not been able to find a job and I have nobody to help me. So I have to do whatever I could to keep body and soul together.

Chima was able to find his way when they got to the bus stop. His dislocated wrist had swollen. He went to a chemist shop to massage and bandaged the wrist. The next day he came out very early in the morning, and yet there were no buses on the road. The bus stop was already filled up with passengers. Two hours later, one Molue, a 911 Mercedes converted into a passenger lorry, came coughing and sneezing. The inside was filled up with passengers surging out of the doors and yet more people were still jumping onto every available space on the body of the Molue without it stopping.

As the Molue was passing Chima jumped with all his strength, slipping his injured right leg. The passengers on the door grabbed and held him until he found a place and dug in his left foot. The bus got only as far as Oshodi. From there he followed groups of other trekkers to Ikeja.

‘I was here yesterday to see Mohammed. He told me to come back today,’ Chima told the armed mobile policemen at the gate. They passed him and he walked down to SARS department.

The same man who had first begun to beat him was at his duty post. He recognised Chima. ‘Mohammed is not around,’ he said sternly to Chima.

‘Can I wait for him?’

‘Go and sit down there,’ he pointed to a bench under a mango tree.

It was not until afternoon before Mohammed drove in with the same pickup van. As he was coming out of the vehicle Chima walked down to him.

‘You are here again today,’ he said. ‘Do you have the money?’

Chima shook his head. ‘Sir, my father just died and we don’t have access to the little money he has in the bank.’

‘Ok. Go and look for twenty-five thousand.’ Mohammed said and walked away.

‘Please sir,’ Chima said, following him.

‘You’d better not follow me. And don’t come here again if you don’t have the money.’

Slowly, Chima walked out of the GID. He went back to the place where he had sat yesterday, under the tree, near the building construction site. He sat down on carton papers left behind by some beggars. For the first time he began to realise that the problem that brought him to Lagos was bigger than him. His money was fast running out and Lagos was grinding to a halt due to the fuel scarcity. And how was he going to get the twenty-five thousand naira?

So Dimkpa is going to die just like that? Tears ran towards his eyes and nose. He folded his head into his knees and began to weep as he had not wept before in his life even when he was a little boy. His entire body was convulsing. ‘God, please help me. This problem is bigger than I can handle. Jesus. I hear you deliver people from this type of problems. Please help me to save my brother. We have no other help. Our father is dead, and no other person wants to help us. Our enemies have destroyed us. Please, God. How can I go back home without my brother? What will I tell my mother?’

Owing to his sorrow, hunger and exhaustion, he fell asleep lying under the cashew tree. Around 6pm he woke up, feeling so strangely peaceful and full of energy similar to the one he had felt, long time ago, on that day he had promised Nne that he would break the door to the university locked against his family.

The whole place was deserted. As he looked towards the building under construction, he saw some men washing their working tools as usual. Perhaps Chukwuma my friend, the economics graduate will be there, Chima thought. He stood up and walked down to the site. His friend was there quite alright.

‘Ah! My friend Chima,’ Chukwuma called out to him, ‘so you managed to come out again today.’

Chima related to him how he managed to get to Ikeja in the morning. ‘Are you not going home? It’s getting late.’

‘If I trek back to Ilasa this night, how am I going to come out again in the morning? There are no more vehicles on the road.’

‘So where are you going to stay?’

‘I am going to sleep here so that in the morning I will continue work.’

‘Is one’s life safe here at night?’ Chima asked, surprised.

‘Does it matter? My life even has no value,’ said Chukwuma.

Chima decided to spend the night there with Chukwuma. Of course, he had no option. It was 2am before they slept on the carton papers Chukwuma had arranged on the floor in one of the uncompleted rooms. The two friends took turns telling each other the story of his life.

‘I have taught in a private school for a salary of five thousand naira only. Everyone regarded me as one who was working. But I could not contribute to the rent of the house where I was squatting. I could not eat a decent meal just for one day in a month. I could not afford even one fairly used okrika clothe throughout the one year I thought in that school. So the best thing for me was to resign and find some other thing to do. That was how I came here and started working as a labourer. For me, this is better than teaching. Which is better: to be clean and perish or be dirty and survive? At least I make five hundred naira every day here.’

‘Five-hundred? That means if I work here like you for about two months, I can save the twenty-five thousand the police man is demanding,’ Chima said.

‘It’s possible. But remember that you have to feed yourself and do some other little expenses out of your daily earnings,’ Chukwuma reminded him.

‘Yes. But at least I will be close to that figure.’

‘Yes.’

‘I will start in the morning.’

‘But you have an injury on your right hand.’

‘I will manage.’

In the morning Chukwuma introduced Chima to the foreman. ‘But how can he work with that kind of hand?’ the foreman asked.

‘Sir it’s only a minor injury. I can work with it sir.’

But his friend Chukwuma knew it was not by any means a minor injury. He helped Chima in every way he could. He shoveled gravel into Chima’s head pan and helped him put it on his head. So also they did with every other material they had to carry to the bricklayers. Throughout that day pains exploded from his injured hand but Chima gave no single sign capable of betraying his suffering.

They were asleep that night when they heard gunshots. Some men ran into the uncompleted building followed by another group of men spraying bullets all over the building. Chima laid flat on the floor wedging his head into a nearby stone. But Chukwuma, on hearing the gunshot and seeing men running into the building, jumped up trying to run out of the building. The bullets cut his body into pieces. He shouted, fell down, and laid still.

Then strong flashlights converged on Chima and a very strong voice shouted: ‘don’t move! Hands up!!’

Not knowing which of the two contradictory orders to obey, Chima decided it was safer to remain still. A jackboot hooked to his neck and crushed his head to the floor. Chima shouted.

‘This one is still alive!’ the owner of the jackboot on his neck shouted

‘Sit up!’

Chima raised his two hands and slowly sat up. Swiftly, a pair of handcuffs locked his two wrists together. Then two strong hands on each of his shoulders hauled him up roughly and dragged him out of the building into a waiting police vehicle.

Once again, Chima found himself in the midst of detained criminals in the same cell in the same SARS, GID, Ikeja. He knew he was in a deeper trouble this time. But that was not his problem for now. He had seen Chukwuma jump up, shouted and fell down. Something told him that Chukwuma had been killed – a graduate of economics who could not find a job, five years after school. His family had sold everything they had – land, household properties, animals and everything – in order to send him to school. ‘Since the system does not value my intellectual ability I have to try my physical ability by working as a labourer in a building construction site,’ Chukwuma had told him before they slept last night.

‘Oh! I am tired of living,’ Chima shouted, holding his head in his two hands.

Some of the inmates who were there the first time Chima was brought into that cell recognised him. ‘na the brother of Dimkpa wey them bring here the other day,’ someone said.

‘Where is my brother?’ Chima asked them.

‘They took your brother out yesterday. They didn’t bring him back.’

‘What does that mean?’ Chima asked with a cold voice, narrowing his eyes.

Nobody answered him. Rather, sympathetically, they exchanged glances among themselves.

That means Dimkpa had been executed without trial, Chima concluded.

As early as 6am in the morning the Iron Gate clanged open and Chima was dragged out. They took him to the backyard where over seven dead bodies, all riddled with bullets wounds, laid on the ground. Bravely, Chima walked from one body to another, weeping and hoping to see his brother, Dimkpa, amongst the corpses. Instead he saw Chukwuma’s body and sat down beside him. ‘He is my friend o o o. A graduate of economics who opted to be carrying blocks and cement instead of becoming a beggar,’ Chima cried to the armed plain clothes policemen standing away from him.

One of the policemen spoke to a junior officer. The junior officer raised his gun, aiming at Chima. ‘Please don’t kill me. I am not a thief. Mohammed Mogagi, your colleague here knows me,’ he told them.

The junior officer lowered his gun and looked up to his boss. The boss signaled him to wait.

‘Did you say Mohammed knows you?’ the boss asked Chima.

‘Yes sir.’

‘Go and call Mohammed,’ the boss said to one of his men.

The man hurried out to the office blocks and came back shortly. ‘Sir, Mohammed has not reported for duty today.’

‘Return him to the cell.’

They dragged Chima back to the cell.

It was not until evening before Mohammed reported for duty. He was on night shift. They dragged Chima out again. He could hardly move by himself, not because of the chains on his hands and legs, but due to the pains he had sustained from beatings, hunger, and psychological trauma.

He was taken into a room, a very darkroom, and 500 watts light was focused on his face. It was a torture room. Chima did not see when Mohammed came into the room with other top police detectives.

Mohammed recognised him instantly. Without saying a single word, they went back to the office, leaving Chima alone in the torture room.

Half an hour later they came back. ‘What took you to the uncompleted building where you were arrested,’ the boss asked Chima.

It was a long story. But Chima told them every bit of it with the skill of a creative writer, aware that his life depended on his ability to convince the ruthless police officers of his innocence. ‘We were sleeping at night after the day’s work when suddenly we heard gunshots. We saw some people running into the uncompleted building and another group of men chasing and firing at them. I took cover and pressed my head to the floor. But Chukwuma jumped up. The bullets caught him into pieces. He shouted and fell down to the ground. And I knew he was dead. He read economics at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. His parents are very poor. They are hoping on him,’ he finished and bowed down his head, shaking with tears.

Tears dropped from the eyes of one of the detectives. They went out again, conferred among themselves and came back. This time they removed the handcuffs and chains from Chima’s hands and legs. Still he could not walk. Mohammed supported him and took him to his office.

‘I had speculated I could raise the twenty five thousand if I worked with Chukwuma for two months,’ Chima said to Mohammed when they were alone. In all he had made so far as statements which unknowingly to him, had been tape-recorded, he had not mentioned the twenty five thousand naira Mohammed had asked him to bring and which had led him to join Chukwuma in the uncompleted building.

Although, asking for such gratification from suspects did not constitute any danger to his person or job because it had become an acceptable norm in the force, even among the high ranking officers, Mohammed was impressed with Chima for keeping secret, such a private discussion between the two of them.

‘You have narrowly escaped death,’ Mohammed said to him.

‘Yes, I know.’

‘I am really sorry for what you have passed through.’

‘Thank you, sir. Where is my brother?’

‘I have transferred him to the Kirikiri maximum prison.’

Chima heaved a sigh of relief. At least Dimkpa is still alive, he told himself. ‘Why did you take him there?’

‘I did it for you. He is safer there. Otherwise you will come here one day and won’t be able to find him forever.’

‘Thank you sir,’

‘You are free to go. If you can, come back tomorrow lets take your brother’s case file to the DPP’s office at Alausa. That is all I can do for you. It’s left for you to see the DPP and convince him to advise the court that your brother has no case to answer.’

In spite of his pains and sorrows, joy flooded Chima’s heart.

That was the best news he had received since after the news of his admission into the university.

‘I am very grateful sir. One more thing – can I inform Chukwum’s relations about what had happened to him?’

‘That one is not my business.’

‘I am only seeking your advice sir. Will I be creating any problem for your men if I do so?’

‘What problem? He killed himself. You can let his people know. But I can assure you they will never find his body. I am sure he has already been buried with those other armed robbers you saw lying down there with him. You are a damn lucky chap. You are supposed to be lying down there in the grave with them and nobody will ever have the slightest hint of your whereabouts. ’ Mohammed said, standing up.

Chima stood up too and together they went outside. It was already night.

‘Where are you going?’ Mohammed asked him.

‘Ilasa.’

‘There are no buses on the road. I can drop you off at Oshodi.’

‘I will be most grateful, sir.’

They walked down to the same Peugeot pickup van Mohammed was always driving. The van was covered with tarpaulin. Chima drew up the tarpaulin at the rear and was about to climb in when the high voltage security lights above showed on the piles of arms and ammunitions loaded inside the pickup van.

‘Come to the front,’ Mohammed told him

Chima entered and the van slowly edged out of the GID. They drove silently until Mohammed broke the silence. ‘Are you reading law?’

‘No Sir, Mass Communication and Journalism.’

‘It’s the same thing. I don’t like you guys. You ask too many questions.’

Chima laughed. ‘But I like you,’ he said

‘I like you too.’ said Mohammed. ‘I would have taken you to Ilasa. But you see I am carrying a lot of arms.’

When they got to Oshodi they saw a police patrol van going towards mile 2. ‘Take this guy to Ilasa bus stop. He is our friend,’ Mohammed told the policemen on board.

Chima clambered onto the back of the open patrol van and it screeched away.